The story of a cover: The Broken Road by Patrick Leigh Fermor

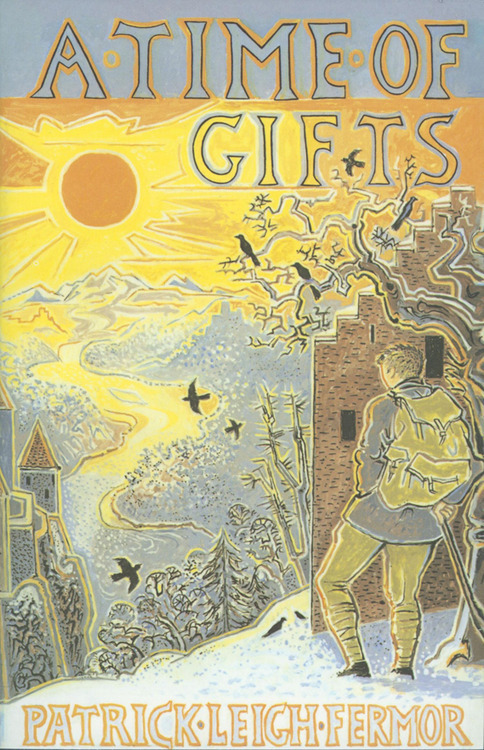

vWhen John Murray scheduled Patrick Leigh Fermor’s The Broken Road for publication in September 2013, its cover posed an interesting problem. Edited by Artemis Cooper and Colin Thubron, (although not a word in the published book was not written by Leigh Fermor), The Broken Road is the final volume of Leigh Fermor’s trilogy documenting his walk across Europe in the 1930s, following his route from Rumania towards Constantinople. The book succeeds A Time of Gifts (1977) and Between the Woods and the Water (1986), and existed in manuscript form, with different corrections on different versions, at the time of Leigh Fermor’s death in 2011. With the exception of A Time to Keep Silence and Words of Mercury, since the 1950s, the covers of his books had all been illustrated by John Craxton; this time the task fell to Ed Kluz.

Art Director Sara Marafini explains: ‘Craxton died in 2009, so when The Broken Road cover was briefed it was necessary to find an artist who would complement the previous look but add their own style and personality, someone who would echo Craxton without imitating him. I admired the work of Ed Kluz and thought his style was perfect as I wanted an artist who would illustrate and also hand-letter the cover as Craxton had previously done. The result is, I think, a beautiful cover that completely ties in with the series but also retains the individuality and originality of Ed’s work.’

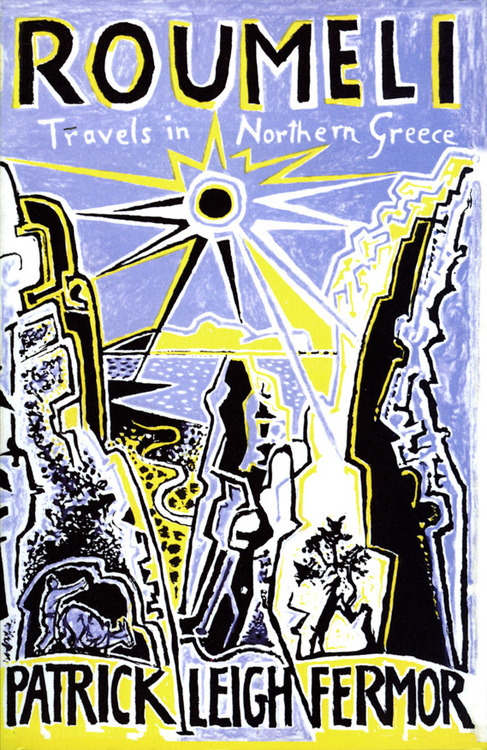

On his blog Kluz notes: ‘Craxton’s bold and playful covers are synonymous with the work of Leigh Fermor. This posed a certain design challenge – I had to ensure that the new jacket sat comfortably within the series whilst expressing my own approach. I referenced the colours of the covers of Roumeli and Mani. Whereas both of these depict a daytime scene with a sun-like motif in the sky, I wanted my design to represent a nocturne. The inspiration for this came from a passage in which Leigh Fermor, accompanied by a stray black dog, discovers the ruin of a mosque at night under a bright moon.’

Artemis Cooper was pleased with the outcome, noting: ‘Ed Kluz, a great choice of artist by John Murray. Ed is very much in the English pastoral and Romantic tradition, like John Craxton who did all the covers for Paddy’s books. I know Paddy would have LOVED it.’

In addition to A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water, John Craxton created the covers for The Traveller’s Tree (1950), The Violins of Saint-Jacques (1953), Mani (1958), Roumeli (1966), Three Letters from the Andes (1991) and In Tearing Haste: Letters between Deborah Devonshire and Patrick Leigh Fermor (2008).

Patrick Leigh Fermor's The Broken Road: From the Iron Gates to Mount Athos was published in September 2013.

In October 2016, John Murray will publish Dashing for the Post, a revelatory collection of the letters of Patrick Leigh Fermor.#

Thing Explainer Treasure Hunt: The Winning Entry

To celebrate the publication of his latest book, Thing Explainer: Complicated Stuff in Simple Words, Randall Munroe – author of What If?, ‘nerd royalty’ and all-round genius – set his fans a challenge: the world’s hardest treasure hunt.

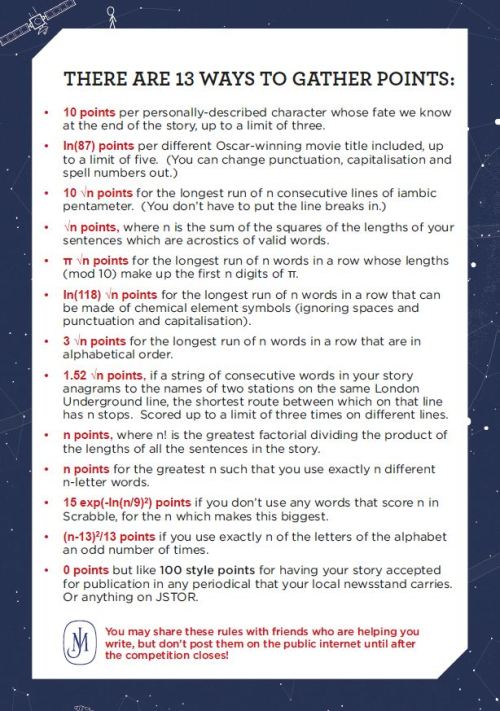

First the distance on the map needed to be plotted from a location touched on in the paragraph about the city. In Oxford it was Merton College (associated with William of Ockham); in Cambridge the descendant of Newton’s apple tree; in Edinburgh the birthplace of Alexander Graham Bell; in Bristol the tower on the Clifton side of the Clifton Suspension Bridge; and in London the Royal Institution where ten elements were discovered. The end destination was a bookshop where they could pick up the rules of the game (see below). Tasked to write a story of at most 250 words, using only the words on Thing Explainer’s list of ten hundred words people use most, XKCD fans rushed to take up the challenge …

And the results were incredible, as you’ll see from the winning entry from Matt ‘Dingus’ Taylor:

A man, alone, removed, his heart confused.

He loves the girl but she another man.

The third, surprised, knows not at all of them.

She wants a beautiful mind. His efforts, less pretty. He ThInKS He CaN WIn HEr IF SHe NoTiCeS HIS BRaInS. IF He PrOVEs He KNOWS ReAsON. IF He CaN Be FUNNiEr. HIS PaInS, ONCe HIS HoPEs, NeVEr PAuSe. He needs to explain things. Cares he almost never can easily say. He often tries, though expects refusing. At last, one new effort.

The third, the reader, the funny sir from across the sea, a man who can say “I give a thing explainer to anyone there who tells greatest imagining”.

However, questions put to him first needed work and then the men agreed word play and language most hard must be used. Why?

The hours pass, his mind, the lettered paths so long circled, thinks of only broken words. Finally, among those torn forms, started a very pleasing picture. A chance to show he sees a beautiful, caring, deep, exciting, funny girl. Heart heavy, his hopes, however, ignored, jokes knocked, love missed, nothing offered or promised, quietly refused. She stays true, until very worn, writing. Yes, even love loses if not grabbed. Cry.

The third man laughs, perhaps, or cries, time continues for him. The girl, an image of a beautiful mind, fades from view. The man, his story written, remains alone, confused. Holding a dream. Another game over.

Finally understanding, chances killed. Tonight he is silent.

Stay tuned for the runner-up entries …

Thing Explainer: Complicated Stuff in Simple Words and What If?: Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions by Randall Munroe are available now.

… and the runners up!

The quality of the entries to the Thing Explainer treasure hunt was outstanding. Here are some of the highest scoring stories. (More to follow!)

Once Mark was eaten,

another bear came down, entering father’s great house. Inside, just keeping

law, mother nodded; offering promises, quickly readying Snow. Throwing up very

watery yellow stomach wine, I watched my sister-brother leave with him. My left

foot would have travelled with the pair, but my legs thought only of poor Mark,

tear drop son, and I stayed by the fire, red like my name for crying. I was

very small then, five by six moons old, and still afraid of the water birds who

controlled the night paths. I had not met the Rain Man, nor the Fire Lady,

flash War Wife of thin attention. (Brain Burner Boy, yes, ages ago; I think

that fun team player has more hats bears can wonder over than any others of the

Green Wood.)

Hot war hours passed, wrapped with worry. Yet I have, I think, forgotten if

kisses dried the tears tracking different winding distances off my sad watering

face. Asleep by bright blue day, the soldiers did return like I dreamed they

would. “Nothing but a good hard walk”, men lied, fixing their deep

green cuts, but we did not press them, for Snow was home. Safe, if not sound.

The stories say Snow White married a large and hairy bear, that he made her

happy, and that Rose Red married the brother of the bear. They say

“her”, and “she”, and call we two “sisters”.

Would that they could use other words for “happy”, ever after.

by Isabelle Adam

A beautiful bird could enjoy flying forever, if its tired

wings were not hurting. Now I can see how deep the thought is. Once there was a

girl I loved. Creatures as humans would not stand troubles of life by

themselves in this tiny world and I am no special case.

It is thirty years ago. We are supposed to marry in twenty minutes. I am running to south gate. Town had many nice places for wedding but this was best. Back then, to my trouble, wedding rings meant a lot. North Bank is behind me a moment later and money for her ring in my hand. I bought one on the way and married the best woman in the world a while later. If ever two were one, then for sure we.

Now it is twenty years ago. Up there she cries holding my youngest son. A lot more water came from her eyes than it should have. Perfect day. Our insides were full of love.

It is today. Not only I hate my mad son because you can hear him enjoying pop music in his room, he also did a terrible thing. That was showing my wife computer games. Since we had a conversation or a warm dinner, it has been at least one year. One could hear only shots during the night. She is just avoiding me. No, I can bear this no more. That is why house is on fire and me on the train, finished.

by Marko Puza

I once saw a girl called Sky.

I was to meet her mother (her father passed away). We reached the apartment. Sky helped Rose prepare dinner.

Rose made art: forest and storm scenes. Yet the place was poor, down, dark. I’d seem scared anyway, so I smoked. It didn’t help, so I put it out. I thought the smokes holder was strange – had not been emptied in ages.

Rose returned – I said I liked her painting of a wood hill. (‘Doing an ok job’ I thought to myself.) I thought Rose liked me. Next we talked about family. I reminded Rose of Sky’s dad - look at his photo over there - don’t you think, Sky?

That’s when I noticed it. The photo was next to the smokes holder. That wasn’t a smokes holder. That was Sky’s dead dad dust.

I had to do something. As soon as Sky was busy I run and fish up that smoke, up out in a rush. I hear her enter and I, for a reason that as of now I am sure was never best, I put it in my mouth. Dead dad dust in my mouth!

I rush out for a walk, a quick cigarette. ‘It really wasn’t the worst, creating cigarette problem. Situation for me, but everyone will forget it. Really, Rose and Sky will laugh if I tell them.’

They didn’t laugh. I no longer see Sky.

by James Manwaring

John Murray and the Costa Book Awards

Andrea Wulf

My book The Invention of Nature: The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt, the Lost Hero of Science has just been shortlisted for the Costa Biography Award 2015. Having spent (far too) many years in archives and libraries it’s utterly thrilling to see the book on the shortlist of one of the most prestigious book prizes in the UK.

In this case my excitement is even greater because I’ve made it my mission to make Alexander von Humboldt known again in the English-speaking world. Born in 1769, Humboldt was an intrepid explorer and visionary thinker – and the most famous scientist of his age. Today, though, he’s almost forgotten in the UK and US. The Invention of Nature is my attempt to restore Humboldt to his rightful place in the pantheon of nature and science … and I’m crossing my fingers that the nomination for the Costa Biography Award will help a little.

Call me superstitious but it all felt right from the very beginning: after all, John Murray was Humboldt’s English publisher in the nineteenth century and now they are the publisher of The Invention of Nature – exactly two centuries after Humboldt’s first book was translated into English. Maybe one day people will once again call Humboldt the ‘Shakespeare of Science’.

Andrew Micheal Hurley

It’s quite unusual to have your first novel published twice in twelve months by two different publishers but it’s been interesting to see how diversely The Loney has been received.

Tartarus Press have quite a precise vision for how they select and sell their books – reviving ‘lost’ works by writers such as Robert Aickman and Arthur Machen, as well as publishing contemporary novels and short story collections which they hope will become, in their words, future classics. For Tartarus, in terms of marketing, The Loney sat within the weird fiction genre and indeed many of the initial reviews came from horror readers and bloggers but they always thought that it was something more than that – a hunch that was acknowledged in Tim Martin’s article in the Sunday Telegraph over Christmas, a quote from which graces the front cover of the John Murray edition. And it’s a feeling that seems to have been expressed in almost every review since then.

The Loney is a horror novel but then again it isn’t. It’s a slippery creature and John Murray has done a great job of capitalising on this very element. Having the novel republished for a much bigger audience has been exciting and at times bewildering but above all it’s just been so gratifying to know that The Loney is being read and enjoyed and that there are people dedicated to making that happen.

Guest blog: A press day with Alister McGrath

As a publicist for the Hodder Faith imprint of John Murray Press, it’s my privilege to spend time with some very brilliant authors and theologians. Each one offers new thoughts and ideas, and an opportunity to consider the world in a different way.

This week I organised a press day for author and Andreas Idreos Professor of Science and Religion at Oxford University, Alister McGrath.

While much has been made of New Athiesm, Alister’s new book Inventing the Universe posits that we are now moving beyond New Atheism and into a period where it is no longer acceptable to conclude that science shuts down faith’s viability. Alister argues the case that science and faith enrich each other.

I love the variety of press that can be covered in a

single day. Alister started the day with the gentle tone of the 7a.m. breakfast

radio show and then went directly to a serious radio discussion with physicist

and humanist Jim Al-Khalili. Alister and Jim have different stances, yet I was

encouraged by the civilised conversation that took place with neither aiming

to discredit the other. Jim even said that he was envious of Alister’s faith

and that religion had been of great comfort to his mother and father, whilst

still concluding that it wasn’t the answer he sought.

We fitted in the next interview on the phone en route back to the office and then went up to our office’s glorious roof garden to meet with more journalists in person. The terrace offers panoramic views of the city and has proven to be an excellent place to take press photographs.

After

all of the press commitments had concluded, we headed out for a lunch with the

whole publishing team. It’s possible for someone to play a crucial part in the

realisation of a book without ever meeting the author, so we always try to make

sure that the whole team gets the chance to speak with the author directly

about his or her work.

The evening’s event was held at the beautiful LICC chapel. Alister is a firm favourite with their lecture-loving crowd so the event sold out extremely quickly. It’s always heartening for a publicist to see a sold out room and a queue the length of the hall developing from the book table. Alister gave a fascinating lecture, opened up the floor and took questions and then signed books afterwards.

This was exactly the kind of press day I love; it makes the most of an author’s time to pack in live radio, pre-records and interviews that will go out in the upcoming days and weeks and it’s especially fun when you get to meet people who are keen to read the book by the end of the day.

Alister will continue to do press in the upcoming weeks and will be appearing at literary festivals over the next year. You can listen to the interview he did for Radio 4 here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06f4z37

Inventing the Universe by Alister McGrath is published on 8 October 2015 by Hodder Faith. For more information follow Hodder Faith on Twitter @HodderFaith

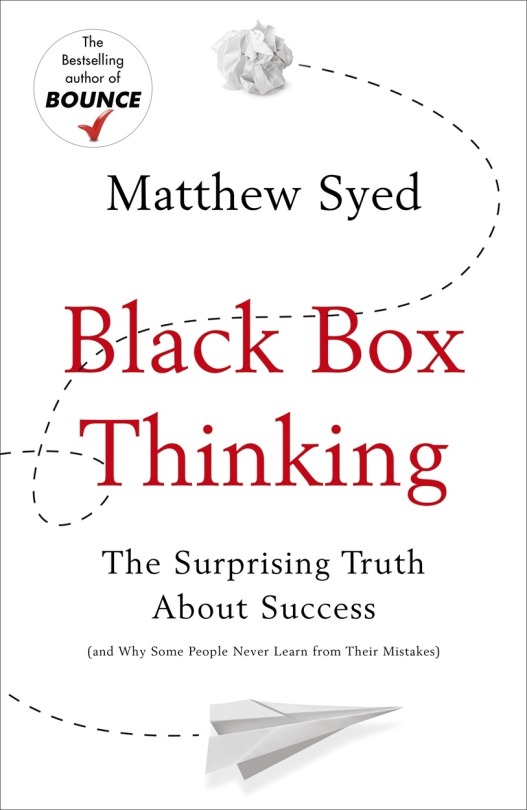

Making a paper aeroplane the Black Box Thinking way.

Over the last couple of weeks, Matthew Syed has gone from stage to studio to sofa to talk about his new bestseller BLACK BOX THINKING. He speaks in a brilliantly insightful and inspiring way about how we should be more open and inquisitive about our failures as a way to success – in politics, business, economics, education, healthcare and our own lives.

On a Friday afternoon in the office, there’s somewhere else I think the ideas in the book could make a difference: paper aeroplane making. One of the plus sides to an open plan office is a clear flight path for some serious competition, so here’s my beginner’s guide to how to make a paper aeroplane the Black Box Thinking way – I’ll take on all challengers…

Use marginal gains: Is your first attempt a nose-diver? How thick is the paper? How about adjusting the fold by a few millimetres? Then maybe try angling the nose a little higher when you throw? Time to stand on a chair? With each adjustment you’ll improve a little, making marginal gains. It may not seem like a lot but it’s this technique that has led to Team Sky’s domination of professional cycling and it was the thinking behind the colour change that made an extra $200 million profit for Google…

Be a connecting agent: If it’s not working, don’t just think of paper aeroplanes, look for inspiration elsewhere – make like Johannes Gutenberg, who invented mass printing by applying the concept behind the pressing of wine to the pressing of pages.

Avoid closed loops: If your plane isn’t flying right, don’t ignore any feedback you’re getting and try to lay the blame elsewhere – in Black Box Thinking, Matthew explains what impact this inability to detect and adapt to error has throughout the modern world: in government departments, in businesses, in hospitals, in our own lives, and even on death row…

Try, try again: As a child, David Beckham practised his keepy-uppy skills for hours every day, reaching a new record of 2003 at the age of 9. It’s a method of persistence that is key to innovation when improving your product too – I’m not sure how much time you’ve got on your hands but James Dyson worked his way through 5,127 prototypes before he got to his world-famous vacuum cleaner…

Think you’ve mastered the skill of paper aeroplane making? Tweet us your prototypes @johnmurrays #BlackBoxThinking

Black Box Thinking by Matthew Syed is out now in hardback, ebook and audio.

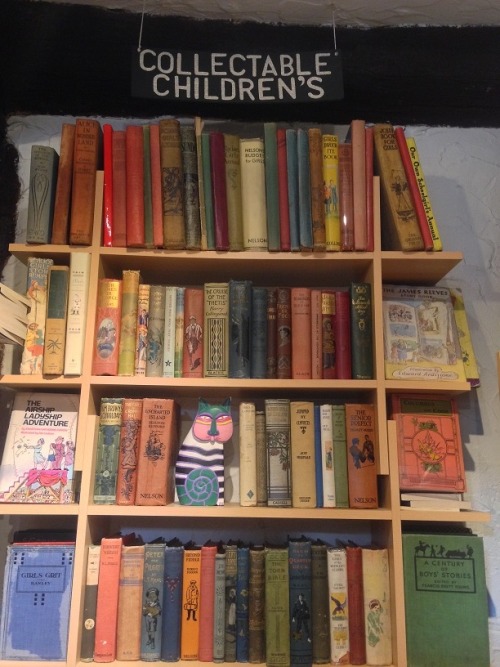

Saltaire Book Shop: the case for shopping locally

On a lovely summer’s day in August, I ended up in North Yorkshire visiting the small but perfectly formed Saltaire Book Shop. You may have heard about them in the news over the past few months: after taking just £2.50 one day, David, the owner, has publicly announced that he will close his bookshop by Christmas if trade doesn’t pick up. As someone who loves visiting bookshops (new ones, second-hand ones, anywhere that sells books!) rather than buying online I had to go and have a chat with him.

The bookshop is full of hidden gems – beautiful second-hand hardback books and pre-loved paperbacks, as well as the usual new publications. You’ll find so much in this shop. I even came away with an amazing print of Masham in North Yorkshire. But my favourite area was the children’s section where David had the most wonderful array of second-hand hardback books all with beautiful illustrations and covers. It brought back memories of my childhood when I’d visit my local library every weekend and then drag my parents round all the bookshops in my town to find yet more Enid Blyton books.

I left the shop with five books – and that was me being good; I could have bought a lot more! Having a chat with David made me realise the importance of local shops in a small community such as Saltaire (or indeed any village or town). David does all his shopping locally and has a good relationship with all the shop owners. He wishes that other people would do the same for books. Talking with him I got a real sense of the passion he has for books and for his shop, and that’s something you don’t get if you shop online. To David, the bookshop is about community: he holds events with local and national authors and is involved in the Saltaire Festival.

David is doing everything he can to make his bookshop a success and I for one really hope the shop is still open after Christmas. If Saltaire Book Shop closes, who knows what might be next and soon you’re left with communities without heart and soul. And you can’t buy that online!

Send us pictures of your favourite local bookshops via Twitter @johnmurrays #indiebookshop

Publicist On Tour: Edinburgh Book Festival

Having studied at the University of Edinburgh I have seen both sides of the city. The ‘quiet’ months that run through winter into mid-Spring see students pass from lecture theatre to library to local pub to home. On weekends, you’ll see fans of the city’s football teams wave their banners as they march down to Leith or hike over to Gorgie. During this time, the Royal Mile is manageable, The Meadows seems spacious and you’ll most likely find a seat or table at your favourite watering hole or eatery.

As spring turns into summer, the mood of the city changes incrementally. End of year exams are dispensed with, graduation frocks are seen on a daily basis, and the erection of a tent in the form of a purple cow is noted. This marks the beginning of the festival season in Edinburgh.

Noticeably the streets swell with revellers and tourists, jovial sounds echo off the ancient buildings and camaraderie between folk from different countries, cities and ways of life prosper. As I stepped out of Waverley train station and made my way to the Edinburgh International Book Festival, I was reminded of what a fantastic place Edinburgh is when the festival is in full swing.

This was my first time at the book festival in a working capacity. Before I had come as a student, moseyed around the square, trying to spot one of my favourite authors but now I was here for work. This meant I could enter the Author’s Yurt.

A low-lit tent, the Author’s Yurt is a hub where bookish people who are appearing at the festival come to mingle, rest, socialise, pass through, converse and watch. I mostly did the latter. Watching as recognised names and faces from disparate circles clashed and mingled. An example: all doe-eyed, I gazed as people such as Jesse Jackson sauntered through, to be met with a ‘Yo! Jesse!’ from Mark Rylance, while I waited for our very own Louise Welsh to appear (who was later introduced to Rev. Jackson).

Seemingly surreal episodes like this are two-a-penny in the yurt and at the festival as a whole. It is testament to the power of the book festival that it can still command such a wide range of names in order to create a diverse and stimulating programme that entertains a keen and engaged audience. I was with a number of authors – a debut author in Andrew Michael Hurley (The Loney), Louise Welsh (Death is a Welcome Guest) who is loved by the Scottish crowd, and Selina Todd (The People) who was speaking on the working class, which is a very current issue. All very different authors in terms of what they were there to talk about and the audience they were talking to, yet the festival is such that it easily accommodates such an assorted range of authors and books. It defies categorisation. Like the yurt and like the city of Edinburgh itself, the Edinburgh Book Festival becomes a place where folk from different cities, countries and ways of life prosper. Until next year!

Michael Rosen’s Good Ideas: A Day with #7yroldme

We live in a world surrounded by all the stuff that education is supposed to be about: machines, bodies, languages, cities, votes, mountains, energy, movement, plays, food, liquids, collisions, protests, stones, windows. But the way we’ve been taught often excludes all sorts of practical ways of finding out about ideas, knowledge and culture – anything from cooking to fixing loo cisterns, from dance to model making, from collecting leaves to playing ‘Who am I?’. The great thing is that you really can use everything around you to learn more.

In celebration of Michael Rosen’s new book Good Ideas: How to Be Your Child’s (and Your Own) Best Teacher, we’ve imagined what a day with our seven-year-old self might be like; where we’d go, what we’d do and what lessons we’d teach ourselves.

The time has come to go on a little adventure back to our childhood home, in a lovely little village perched on top of a hill surrounded by the Italian Alps.

Look! There’s Gio, our big brother: he’s always good fun,

plus he’s five years older which makes him – almost – a proper grown-up (but a really cool one). He’ll happily take a

break from his studies and race you on his bike, and perhaps he might even let

you borrow a book from his collection (Lesson 1: read as much as you can, now

that you have the time). We can sail across the Seven Seas through the pages of

his favourite novel, Treasure Island,

and then build swords out of tree branches and fight to save our treasure.

We’ll probably get a bit dirty in the process (Lesson 2: never wear your good shoes for a sword fight) and Mum might not be thrilled, but we’ll distract her by shouting that Dad is back home from work. We’ll go and welcome him and try and read the news on his big newspaper, the ink staining our little fingers and the great, confusing world out there making us dizzy and desperate to grow up faster.

And finally, we’ll gather around the table and have dinner together, never quite grateful enough for the wonderful food we’re having, but simply content to be in each other’s company (Lesson 3: never let go of that memory).

*

Hello, you. I have a daughter just about your age now, isn’t that strange? Will you come on a playdate with us? Nothing grand; just hanging out in our garden. We’d like to show you the bughouse we put in the tree by the back door. You could help us sprinkle poppy seeds, then add the empty heads to our logpile to make more winter homes for the bugs. Maybe you’ll see the squirrel visit his special nut feeder – though he doesn’t come so often at this time of year. We’ll do some bending and some stretching and jumping, to try and touch the sky. If it rains, we’ll raid the art cupboard and maybe build one of the shoebox houses you love to make. You could help my daughter finish off the dragon she’s creating, help her dad count out the scoops of flour for his baking. Or we could show you how to make a paper star. Because you never grow out of loving to make things, you just stop having quite so much time (and having a daughter is an excellent excuse!). And what will you learn from all of this? That home is where it starts and where it ends. You can travel the world – and you will – but if you look hard enough, everything you need is right here.

*

Just to let you know, your school-report card at age 7 will feature a couple of phrases that will earn a ‘tut-tut’ from your granny. These are: ‘at times, he drifts off into space’ and ‘is prone to day-dreaming’. Oh well, I know the perfect place to drift off into space and day-dream: the back garden.

Standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the neighbours’ back gardens (and eyeball-to-eyeball with the ones across the narrow back lane), we’ll hear snippets of other languages, like the German lady next door who sings while she prunes her roses. We’ll hear passionate arguments between two brothers on who would win a race between a cheetah and a ‘really, really, really, really fast’ motorbike. We’ll lie on the grass and imagine these other lives: how the German lady came to be our neighbour – the trains, boats or planes she took to get here. One day, far beyond the back garden, you’ll meet people from many more places and talk to people with wildly different opinions from your own, but you’ll be able to engage with them. It’s really no different from day-dreaming in the back garden.

*

There’s no greater place to explore than at the beach, so grab your swimsuit. We’ll swim in the sea until our hair is salty and our fingers wrinkle. We’ll float on our backs in the water like starfish and count the clouds. Then we’ll scour the beach for interesting pebbles and shells, which we’ll save for decorating notebooks and jewellery boxes back at home. When the air cools, we’ll head indoors to read and write stories, transporting ourselves to imaginary worlds populated by fairies and pirates, where gardens are always secret and even the humblest of 50 pence pieces have magical properties. The wisdom of childhood will be exchanged for the lessons of adulthood. You’ll teach me how to do cartwheels, the best way to draw castles and all the Spice Girls routines, and I’ll tell you that violins are cool, that there’s really no reason to be scared of dogs, and that the time will come when your little sister will have lots of really good clothes, so be kind.

*

I loved nothing more than being in the countryside when I was a child – despite being brought up in the city – and I think if I went back to meet my seven-year-old self, I’d probably like to take off on a long walk together. Pointing out which farm animals we could see on the horizon, chasing the dog to the next tree and then the next one, and stopping to feed a horse some sugar cubes we’d brought with us and kept in our pockets. We’d talk to all the animals that we passed on our way and make a mental note to tell my parents all about each and every one of them when we got home. I was sometimes made to feel a bit silly by my friends for enjoying being on my own and obsessing about nature, but I’d like to reassure my seven-year-old self that there is absolutely nothing wrong with that. In fact, you don’t get enough time when you are older to do that, so just keep on exploring!

*

I’d give you a leg up over the high brick wall surrounding our garden and we’d go exploring. We’d name and count all the different types of trees around us and gather the berries nestled within their leaves (never eat the red ones, I’d warn, only strawberries and raspberries, and it’s never a good idea to touch the mushrooms either). We’d keep an eye out for small bugs and animals scurrying around beneath our feet, seeing who could spot them first; our own game of I-Spy. Once out of the woods we’d rush past the castle looming ominously above us in the gathering dusk. I’d tell you about Thomas FitzAnthony, the man who used to live there and how he founded our town in the 13th century, and about the time Oliver Cromwell and his troops attacked. We’d pause for a moment, trying to imagine what it must have been like, and then, on down to the river where we’d set up our fishing rods and make ourselves comfortable in the gathering gloaming, waiting for that first bite. I’d whisper that you should try and be more thankful for what you’ve got – one day you’ll move away from the country to live in a big city and it’s only then that you’ll start to appreciate the clean air, twinkling stars, green fields and silence. You’ll even miss the cows!

*

This summer, one of the things I loved doing with my four-year-old nephew was taking him on treasure hunts around the huge garden and barn at his parents’ house in the Yorkshire Dales. So, if I were to spend a day with my seven-year-old self, this is how we’d spend it. We’d learn how to read a treasure map, what the clues were, which trees we had to pass and how to make sure the map was the right way up. We’d walk through the fields, trying to make a whistle with the long blades of grass, then through the orchard to check if the apples and pears were ripe yet, and up to the cricket pitch to make sure the grass wasn’t growing too long and that Baby and Sam (the dogs) hadn’t eaten all the tennis balls. We’d then stop and make sure we were on the right track, consult the clues again and there it would be! A giant pirate flag concealing a miniature treasure chest. We’d run up to the house to open the box and find out what we’d uncovered, and spend all afternoon eating the gold chocolate coins and reading the book that we’d found inside. And then we’d go to bed, dream about buried treasure … and do it all again in the morning.

Good Ideas: How to be Your Child’s (and Your Own) Best Teacher is published in paperback on 13 August 2015.

Get involved on Twitter! Let us know what you’d tell your seven-year-old self to win a signed copy of the book: @johnmurrays @MichaelRosenYes #7yroldme

A novel point of view: Debut author Paula McGrath on why short stories are sometimes not enough

Unless you’ve been living under a rock you will have noticed that the short story is enjoying something of a resurgence. I love short stories, and felt very fortunate to have Éilís Ní Dhuibhne, one of the best practitioners of the form, as my MFA tutor. She was partly the reason why, when asked what I was working on for my thesis, I announced that I was writing a collection of short stories. This was a lofty declaration, considering I had written only one decent short story to date, about a squabbling German couple with a baby, as observed by a character called Joe as he tended his farmers market stall in Chicago.

I was persuaded to write more about Joe, but because he was an enigma who didn’t like to give anything away, I did so from the perspective of Yehudit, his mother. Carlos, his Mexican employee, got a story next. Gradually, the book began to grow and, while the stories themselves maintained their autonomy – fulfilling the short story criteria of concentration and limitation, and Edgar Allen Poe’s famous ‘unity of effect’, new stories and characters persisted in making connections to the first story, and to each other. It was beginning to look a lot like a linked collection.

But the links became more numerous, and then one story took off and couldn’t seem to stop. When it crept past The Dead’s 15,000-odd words, I decided it was time I did the research. Novels-in-stories, short story cycles, composite novels, polyphonic novels. Whatever these sort of books were called, it had become clear that I was heading into novel territory. I investigated my bookshelves and, sure enough, it was territory I was familiar with: Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club, Anne Tyler’s Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant, Colm McCann’s Let the Great World Spin, David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge, Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad were all there, to name just a few.

I liked these sort of books, and had long been attracted to them. But what was this attraction to novels which managed to be both disconnected and linked, to somehow contract and expand at the same time? The American author Michael Chabon says that they can ‘create an effect you can’t get from a novel or from one story alone’, and I agree, but what was this effect?

Around the time that I was searching for solutions to my formal dilemma, Commander Hadfield began tweeting his stunning photos from space, presenting us with unimaginable views of ourselves, and I was helpfully reminded of Robert Altman’s Short Cuts, the 1993 film based on Raymond Carver’s short stories and transposed to LA, where ever-present medfly-spraying helicopters hover over characters whose lives intersect only loosely. I remember coming out of the cinema thinking: so that can be done.

In the 19th-century novel, omniscient narrators knew the thoughts and feelings of all of the characters. In Pride and Prejudice, for example, Jane Austen focuses on her protagonist, Elizabeth, but her narrator delves into the minds of many of the other characters, as well as maintaining an overview which might be read as Austen’s own voice. Then, for a variety of reasons – Darwin’s theory of evolution, perhaps, or the Great War, both of which added to the collapse of the idea of absolute knowledge and the rise of the individual – the all-knowing, god-like narrator fell out of use. To paraphrase the critic James Wood, the standard third-person omniscient narration had become a kind of ‘antique cheat’.

Other modes of narration grew in prominence, including fragmented tests, multiple perspectives, and the linking of multiple perspectives. Alternative methods of providing an overview were sought, and these could be combined with linked multiple perspectives to create a whole greater than its parts. The helicopter achieves this overview in Short Cuts, the tightrope walker in Let the Great World Spin. Adam Johnson uses a drone in his EFG Award-winning story, Nirvana. In my novel, Generation, overview is provided through the uranium mines and space race of the opening chapter (and the allusion to Commander Hadfield’s tweets that I couldn’t resist), and the circular return to the mine at the end.

But, with all literature, overview is ultimately provided by the reader, and it would be a mistake to underestimate what she is capable of. Well-versed in a range of narrative methods from literature and film, the modern reader is used to making jumps in time and space, and filling the interstices between. This is probably the single-most reason I am attracted to fragmented texts and linked narratives; I feel a little bit cleverer when the writer trusts in my ability to traverse the narrative, however difficult.

As readers, we can zoom in to engage with the interior life of an individual protagonist, then move across to another; we can zoom out to connect these individuals to each other within the world of the novel; then we zoom out further still, where we recognise the insignificance of the characters’ concerns, and of the characters themselves – and of our own concerns and, indeed, ourselves – when viewed from a distance. But however insignificant we may appear when viewed from outer space or from the distant future, we are spared from a descent into nihilism, because we know that we still have our connections to each other, as well as to the generations which came before us, and which will come after.

Paula McGrath’s first novel, Generation, is published by JM Originals on 30 July 2015, alongside An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk, According to One Who Saw It by Jessie Greengrass.

This piece was originally written for and published by The Irish Times. Used with permission. http://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/the-evolution-of-storytelling-an-overview-1.2302135

Drüben: Rediscovering Motherland

On 9 November 2009, twenty years after the fall of the Wall, the spotlight was on Berlin. It was a night of dramatic gestures: concrete slabs dominoed down the border strip. Mikhail Gorbachev and Lech Walesa bear-hugged as if they’d always been the best of friends. Angela Merkel and a cast of heads of state stood at the Brandenburg Gate and took a bow for the end of the Eastern Bloc. The world’s press gave the spectacle spectacular reviews. Everyone was here, the whole city.

Except me. I was in bed, lying in the dark, pretending it wasn’t happening.

It wasn’t a boycott. It was The Method. I was being Jess – the protagonist of my novel and a teenage believer – living truthfully under imaginary circumstances. When Jess steps onto a frozen lake and off the last page of Motherland, it is 1984. The Berlin Wall is intact and, as far as she knows, will stay that way forever. It was one of the hardest parts of the project: unknowing the fact that within five years that future would be finished.

When I landed in Berlin in June 2009, I wasn’t yet in character. I stepped off the plane as Jo McMillan, bringing with me a few ill-formed questions and lots of blankness. I didn’t know much about the GDR. The facts I’d once kept at my fingertips, I’d long since made a point of forgetting. And I didn’t know how I felt about my past except that perhaps I’d dreamt it.

I rented a flat in west Berlin. This was drüben*, and my first encounter with the other side of the city. An unrenovated tenement, hanging on by the thickness of its dust to the face of old Berlin. On the hottest days, I smelt gusts of warmed-up sewage; not the smell of socialism after all, but the stench of blocked drains. I lived between the Wagners and the Grimms, who’d been there forever, seen Berlin whole and divided and then whole again. The border was at the end of our street, the Wall Trail marked in the tarmac. If I leaned over the balcony, I could see into the East. My past was beyond that line, a hundred metres away.

‘A book about the East?’ Frau Grimm said, working her jaw and tipping cold tea over her geraniums. ‘It is gone. There is nothing else to say.’

For a week, I tight-roped this side of the border till I could summon the nerve to step into the world of the story.

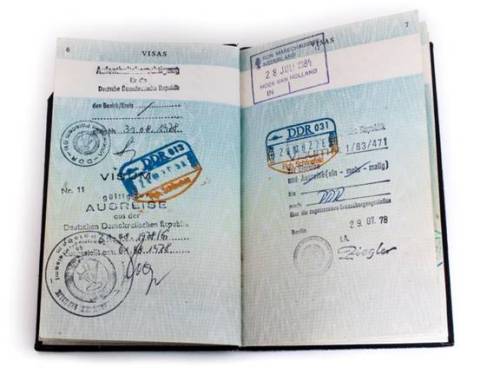

DDR visas (1978) from

my old passport.

On the set of Motherland, nothing appeared to have changed. At a distance, the landmarks I knew were all still there. But then I got up close. At the Brandenburg Gate, you could now Segway past make-believe border guards. The TV Tower – that crystal ball in the sky – had a Fitness First and a casino where once there’d been a model of Marzahn. The Marx and Engels on Alexanderplatz were put in a corner and turned to face West. And the Palace of the Republic, where my mother and I had raised many a glass of Rotkäppchen, was turning into a Prussian Schloss. There was a DDR Museum now. Children who’d been born simply German sat in the Trabant and steered the wheel to nowhere. The GDR was in a museum. And a museum was where you kept dinosaurs and dead things.

East Germany was gone, but I had to bring it back to life for Motherland. I needed witnesses and many of them had gone. They’d died, moved on, reinvented themselves and changed their name. But I tracked one person down: the woman who’d directed the Potsdam English Summer Course. She was the closest I’d ever got to a Party apparatchik and the woman who inspired the character of Saskia in Motherland.

I found her on the internet; a member of her Kulturverein, her interests listed as ‘discussions and Cuba’. I sent her a card – one with red carnations – and told her I was writing about the GDR. Would she be willing to talk?

Early the next morning – straight after the post – my phone rang. ‘There is so much to say. And I will tell you everything.’

She started with the end.

On the night of 9 November 1989, she wasn’t watching as Günter Schabowski fumbled in his pocket for a note and announced to a press conference that, as far as he knew, the border was now open. Instead, she was on her way to Weimar for the Schiller Festival (it was the 230th anniversary of Schiller’s birth the following day), and she wondered why the platform for west-bound trains was so crowded. She recalled how, when she heard the news, she had, ‘just hoped I would not be strung from a lamp post’.

She’d witnessed many ways to die. She’d been through the war. In Nazi Germany she’d hated the Russians, but then they won and overnight the Russians became the East’s greatest friends. She’d survived every twist and turn of the twentieth-century. And how?

‘I knew what people wanted and I gave it to them.’ She knew what to say, and when. She had her role and played her part.

I’d never heard her speak like this – unguarded, without her script. But then she knew, and I didn’t, that she had cancer and that six months later she’d be dead.

The end of my street,

Kopenhagener Straβe.

I still live in Berlin. I rent a flat a hundred metres from the border, just inside the East. No-man’s Land is at the end of my street. It has been turned into a park with an amphitheatre and, on summer Sundays, there’s outdoor karaoke. Most weeks a man with a tucked-in shirt sings ‘My Way’ in German and brings down the house.

On 9 November 2014, on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Wall, I wasn’t in bed pretending. I stood on the steps of the amphitheatre to get a better view. I raised a glass of bubbly as lights lit the underside of clouds, as the balloons went up, as the Wall came down, as the curtain rose on Motherland.

Motherland by Jo McMillan is published on 2 July 2015.

*Translation: over there; on the other side

Terry Stiastny on Writing Journalism and Writing Fiction

‘One day, perhaps, they will move to Berlin; the contingency, even in Bonn, is occasionally spoken of. One day, perhaps, the whole grey mountain will slip down the autobahn and silently take its place in the wet car parks of the gutted Reichstag.’

John le Carré wrote this of Bonn, the small town in Germany when, in 1968, such an eventuality seemed implausible. Thirty years later, that contingency was a reality. Germany’s capital was on the move, with fleets of lorries carrying boxes of files along the autobahns from west to east. Politicians, diplomats and civil servants moved and journalists followed them. I was one of the journalists.

In 1999, I spent a fair bit of my time in the wet car park of the now-renovated Reichstag. That’s one of the things people neglect to tell you about journalism: you spend a fair bit of time in wet car parks, though most of them are not nearly as fascinating as that one. Norman Foster had shown us round the new building before the German politicians took their seats: the glass-and-mirrors dome, the stonework cleaned to reveal the graffiti left by Russian soldiers at the end of the war. My BBC colleagues and I marked out our space on the metal grandstand that gave us a view of the opening ceremony and guarded our gaffer-taped demarcation fiercely.

As with the building itself, at that time Berlin was an intriguing mixture of the new and the uncovering and remembering of the old. The British Embassy was being topped-out – a modern building restored to its pre-war site. We talked to former dissidents and former spies. The consequences of the recent past often flared up in German politics: the former Chancellor, Helmut Kohl, was accused of having had removed from the archives records of his conversations, which had been bugged by the East German Stasi. Commentators described those who escaped public scrutiny of their Cold War choices as having ‘the mercy of a western postcode’.

There was so much going on that it was easy not to follow some stories through, or never to be able to get to the bottom of them. One such was the tale of the discussions between Britain and Germany over what should happen to Stasi files that Britain held; files which had been spirited away in the confusion after the fall of the Wall and the collapse of the old East German regime. The names contained in them hold the key to the identities of informers in the West. As far as I know, to this day the files have never been returned. Perhaps with more diligence, I’d have found out what was really going on. Instead, as I moved on and back to London, I almost forgot about it, in the same way I forgot about so much old news.

Somewhere along the line the story came back to me – not as the subject of a journalistic investigation, but as a way of asking ‘what if’? What does it mean to have the mercy of that Western postcode? How are the moral choices that people and politicians make in Western democracies different from those of people who don’t have the luxury of freedom? How was the view I saw from the riverside terraces of Westminster different from the ones I’d seen in Berlin?

In Berlin, anyone who felt homesick for Bonn could – and still can – spend their time in the Ständige Vertretung restaurant, named after the Permanent Representation of West Germany in the old East, a place full of old political posters and photos, just across the river from the new Parliament. It was a place that created a nostalgia in the same way that other bars in the old East created theirs in Communist kitsch, red stars and bits of old Trabants. It’s now fifteen years since I worked in Berlin, twenty-five years this year since the Wall came down. It already seems like a bygone place and time, almost as far distant as le Carré’s Bonn and Berlin. But what I found I missed, as I wrote this book, was that sense of optimism about new beginnings, even in the knowledge that the past which lay beneath them was full of complications.

Acts of Omission by Terry Stiastny is published in paperback on 7th May 2015.

Images © Shutterstock

Writing our own Simple Rules

Life is far too complicated and seems to be getting more so every day. What I liked so much about Simple Rules is that it doesn’t take a one-size-fits-all approach – there’s no magic bullet for complexity – what Donald Sull and Kathleen Eisenhardt do in this book, clearly, sensibly and entertainingly, is show you how to solve your own problems, by making your own set of simple rules.

Don and Kathy have tried and tested their guidelines on businesses all over the world – and their advice works. Full of fascinating examples from how French women don’t get fat (eat exactly what you like – only less of it) to how to survive a forest fire (turn towards the fire and head for where it is thinnest) and packed with business secrets from companies ranging from Apple to Zumba, Simple Rules is an eye-opening, game-changing book.

So at John Murray Press on publication day, we wanted to start the ball rolling to share our simple rules with you. I’ll start. As an editor, I am deluged with manuscripts and proposals and emails. And everyone around me is too. So my simple rule for making my book or idea stand out from the crowd: FIND THE STORY.

Simple Rules is published on 7th May 2015. We’d love to hear how you deal with life’s complexities –

follow @johnmurrays on Twitter to share your #SimpleRules.

Jonathan Beckman on Marie Antoinette, handwriting and the Paris archives

It’s obviously a pleasure to see my book in its finished form – the safe delivery after a prolonged pregnancy. It’s also an oddly alienating one. Laid out on the page, the words suddenly seem, well, not mine any more. Not at all in a bad way – printed in Bembo, well-leaded, well-kerned, with generous margins, they look suave, muscular, authoritative, dare I say? This was not how I felt while writing them. I work in Scrivener, a brilliant program for organising notes and drafts. Suffering from an innate conservatism that on a bad day might be taken for congenital laziness, I did not change its default typeface from Optima. It’s a bleak sans-serif, inoffensive, perhaps, but lacking in any personality (I was not surprised to discover that it had enjoyed a seven-year spell as the chosen font for Marks and Spencer’s internal correspondence). As I wrote, it seemed to thwart my sentences as they strove for elegance. However much I polished them, Optima turned them dowdy. Halfway through – and a software update later – the default typeface had switched to Cochin. Now I was presented with the opposite problem. Cochin was so imposing, so elegant that had I typed up the football scores they would have sung like poetry. Cochin’s italic ampersand is such a thing of fluid beauty that I had to restrain myself from gratuitously inserting irrelevant book titles or names of ships. Every word looked gorgeous in Cochin, but were they any good?

We do judge books by covers and we judge words by their physical appearances – their cursiveness, their ligatures, their line. Through the writing of How to Ruin a Queen my emotional temperature has been tied to the look of words. It has fallen and risen as they’ve obstructed my understanding or revivified a dormant world. This seems particularly appropriate for the Diamond Necklace Affair, a story that hinges upon a series of forged letters: the cardinal de Rohan, previously Marie Antoinette’s sworn enemy, believed he had received letters from the queen assuring him of forgiveness and promising him high political office. At the very heart of the Affair sits a bill of sale for an immensely expensive diamond necklace signed, everyone presumed, by the queen herself.

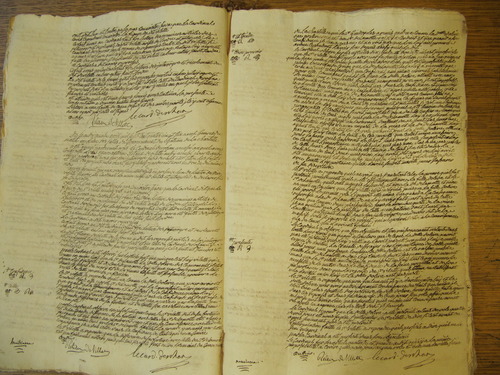

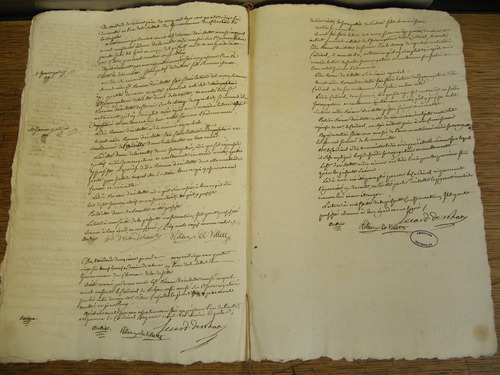

I went to Paris in the spring of 2010 ready to immerse myself in the documents related to the Affair. Eagerly, I opened up the box filled with the witness statements and cross-examinations about the necklace’s disappearance, and I nearly cried. The page was aswarm with indistinguishable letters in densely packed lines which wriggled out of my understanding like a haul of sprats. Was that an a? It might equally be an e or an o or an n. Ds looked like ps; fs looked like ss; anything with a descender below the line required a stab in the dark. And there were dozens of pages, hundreds of thousands of words, to pick through in order to hear the truth behind the cacophony of claims and counterclaims.

More experienced friends reassured me that I would get my eye in. It happened little by little but, before long, I began to recognize that what had previously appeared to be twelve loops followed by a t:

were, in fact, the words Ce moment. As I sank deeper into my research, I learned something of the man whose handwriting I was struggling over. His name was Frémin and, according to Rohan’s fixer, Abbé Georgel, he passed transcripts of interrogations to Rohan’s legal team that they had no right to see. In the memoirs of Rohan’s adversary, Jeanne, comtesse de La Motte-Valois, I read that Frémin had been deliberately obstructive, emending her words as he took them down. Ludicrous paranoid fantasies render Jeanne’s work largely unreliable, but she was not wrong in suspecting Frémin of working against her.

Towards the end of the trial, Frémin and his heavy-inked words, like knotted curls of hair, disappeared, to be replaced with a much more refined script composed of flicks and touches, as though the writer wished his pen to spend the least amount of time possible touching the page. Had Frémin, I wondered, finally been caught leaking papers and dismissed? Or was there some more prosaic reason for the change of clerk? One fragment I read suggested that Frémin had been replaced by Monsieur Mouton, his brother-in-law, as Frémin was too chatty and worked at half the pace of other clerks. Yet, if this was the reason, it’s strange they waited until the last few days of hearings to dump him.

By the end of my research, I was managing to wring sense from the scrappiest and scratchiest of hands (these were normally government ministers, who had secretaries to call on when they needed to write neatly). I even had a go at deciphering the letters in invisible ink – the words now faded to rusty smudges – that Rohan had smuggled out of his cell.

Archival work can be arduous and mind-numbing and infuriating, but there are moments that bring you up short. On my first morning in the National Archives, I ordered up the wrong box of documents. I knew this as soon as I opened it – it was, as I recall, about some agricultural matters – but I took out the first sheaf of papers and leafed through them anyway. At the bottom of the final page were a number of signatures. One of them, unmistakably, was Robespierre’s. The document must have been signed off by the Committee of Public Safety, one of thousands dealt with in those months of furious energy as the Revolution came to a head. Now, as I stared down the gelid executioner of so many innocent Frenchman, I felt that our encounter on the page was far more intimate than any stage-managed one that might be had with a living politician or celebrity. It’s at moments like these that you feel, almost physically, history creeping up behind you and tapping you on the shoulder.

How to Ruin a Queen: Marie Antoinette, the Stolen Diamonds and the Scandal that Shook the French Throne by Jonathan Beckman is published in paperback on 23rd April 2015.

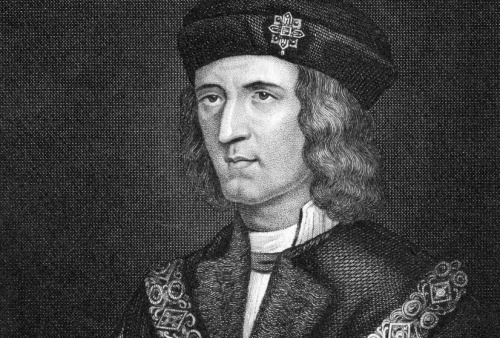

Looking for Richard: Philippa Langley on discovering the lost remains of history’s most controversial king

On 22 August 1485 Richard III was killed at Bosworth Field, the last king of England to die in battle. His victorious opponent, Henry Tudor (the future Henry VII), went on to found one of our most famous ruling dynasties. Richard’s body was displayed in undignified fashion for two days in nearby Leicester and then hurriedly buried in the church of the Greyfriars. Fifty years later, at the time of the dissolution of the monasteries, the king’s grave was lost – its contents believed to be emptied into the river Soar – and Richard III’s reputation buried under a mound of Tudor propaganda. Its culmination was Shakespeare’s compelling portrayal of a deformed and murderous villain, written over a hundred years after Richard’s death.

In the week that sees Richard III’s rediscovered remains reburied at Leicester Cathedral, Philippa Langley, who led the search for his grave, looks back on this momentous occasion.

The re-interment of Richard III on 26 March 2015 marks the end of an extraordinary ten-year journey, which started in the most unlikely of locations: a car park in Leicester. It was here, in 2005, that I first realised that finding Richard’s grave, which had been lost for over 500 years, was a real possibility. That visit changed my research focus from Richard’s life, to his death and burial, and was the impetus for four more years of intensive research, fitted in around work on a screenplay and the demands of single-parenthood.

The breakthrough in the Richard III case had come when, in the summer of 2005, Dr John Ashdown-Hill announced his ground-breaking discovery of Richard’s mtDNA sequence. His discovery meant that we would be able to identify Richard’s remains, if we found them. The question was, where was his body buried?

Philippa and her co-author Michael Jones in the field at Bosworthwhere they believe Richard III died.

In search of the answer, I visited the Richard III Society archives, where I found several journals from the 1970s that speculated about the present location of Richard’s grave in the now-vanished Greyfriars Priory, an area now occupied by car parks. It was widely believed that Richard’s grave had been desecrated in the sixteenth century and his remains thrown into the river Soar, meaning that a search for his grave was pointless. However, there were some that disagreed, including Audrey Strange, who put forward the compelling case that this story of Richard III’s remains had become confused with the remains of John Wycliffe, the Bible reformer, which had been dug up, burnt, and thrown into the river Swift in nearby Lutterworth in 1425.

In 2007, a small archaeological dig in the location where two local historians placed Greyfriars Priory found nothing of significance. But my research suggested that they had placed the church too far east. One

of the people I contacted at this time was Annette Carson, whose book Richard

III: The Maligned King (2008) was the first I had read which, in

addition to stating there was no reason

to doubt Richard’s body still lay where it was first buried, also argued that

this was probably ‘beneath the private car park of the Department of Social Services’ where our dig eventually took place.

In February 2009, after years of research, I took the momentous step of setting up a coherent project, which I called the Looking for Richard Project. The team grew to include a distinguished list of Ricardian experts in a variety of fields, including among its founding members Dr Ashdown-Hill and Dr David Johnson, and, on her return to England, Annette Carson. Now I had to amass the evidence to convince everyone else that an excavation would be productive. These were 3½ years of pioneering research, planning and re-planning, investigations and radar surveys. They were also years of writing, telephoning and knocking on doors and getting permissions from landowners, not to mention convincing the City Council to close a busy car park for 3 weeks.

Philippa at the dig in Leicester in 2012.

Finally in 2012, our research proved accurate. Richard III’s body was located.

We had begun where the study of our past always begins, with open minds and questions. Never a trophy hunt, the search for Richard III’s body was undertaken for neither gain nor glory, but as a respectful attempt to give honour to a king badly served by history. This year we commemorate finding Richard III – who knows what more is waiting to be discovered? Certainly the study of late medieval history will never be the same again.

You can read more about the Looking For Richard Project and about King Richard III in The King’s Grave: The Search for Richard III by Philippa Langley and Michael Jones, in Finding Richard III: The Official Account and at: http://looking-for-richard.webs.com/